The 5G, reminder of the context¶

Authors and date

- Submitted on: April 13th 2021

- Gauthier Roussilhe; Designer and PhD student; RMIT, CRD (ENS Saclay, ENSCI)

The 5G, reminder of the context¶

5G is an evolution of mobile telecommunication protocols. These evolutions are generally thought at 10-year intervals, so 5G started to be developed around 2008-2009. This new protocol is advancing on three different fronts: increasing mobile bandwidth, reducing latency and managing millions of connections per square kilometer. These developments are part of a logic that foresees the development of connected and "smart" cities through the deployment of thousands of sensors and connected devices, more or less autonomous vehicles and, overall, the increasing digitalization of everyday life.

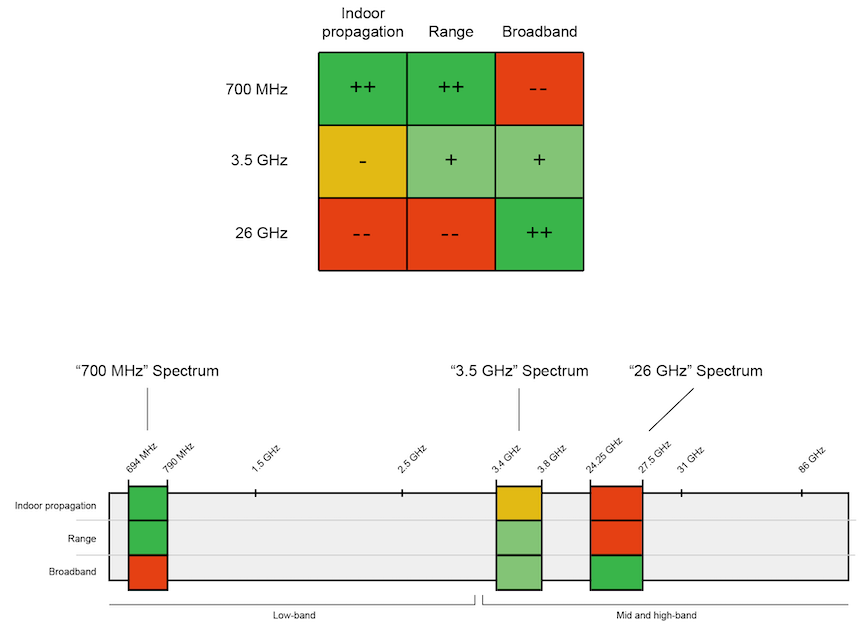

From a more technical point of view, 5G covers three different frequency bands: 700 MHz (formerly allocated to DTT), 3.5 GHz (sold by the French government in October 2020) and 26 GHz which has not yet been allocated. There is a simple relationship to remember: the stronger the signal (in terms of data transmission) the less range and penetration. The second relationship to understand is that a radio station is just an access point to the fiber network, an antenna only performs the transmission to a mobile device on the last few hundred meters (last-mile delivery). So the bandwidth gain is only over this short distance, the rest depends on the fiber network and the connected data centers.

Comparative table of the different frequencies of 5G1.

Why 5G is controversial today? It is not so much the technical standard that is debated than the massification of an infrastructure on a national and international scale without public consultation. The development of this infrastructure has rarely been interested in public decision making, so why now? Several phenomena are at work. The rise of the climate emergency is creating a new prism for analyzing all political choices. Secondly, this debate shows the reintegration of technology in the political sphere. Indeed, technological choices are once again beginning to be seen as societal choices. We will focus here on the intersection of transition policies and technological choices. This prism of analysis can then be formulated as follows: how does 5G fit into the trajectory of a desired world stabilized at +2°C?

Estimating the environmental impacts of 5G¶

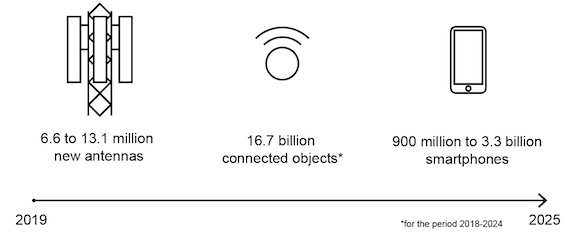

The question of environmental impacts can be approached from different angles. One can focus only on the power consumption of the hardware and its efficiency, but this is a very partial view. The impacts must be assessed during the manufacturing and operation phases in relation to several environmental factors: primary energy consumption, greenhouse gas emissions, resource and water consumption. First of all, it is necessary to know the additional equipment that is added and its manufacturing impacts: does a 5G antenna have more impact during manufacturing than a 4G antenna and, above all, how many new stations and antennas will be added or modified? How long will they last and how will this affect the life of the previous fleet (3G/4G)? The same question can be asked about smartphones. The transition to 5G implies a renewal of the mobile device fleet. Does a 5G smartphone have more impact during manufacturing and how does 5G accelerate the renewal of the fleet? Same question for connected objects and sensors, laying new fiber, etc.

Estimated net manufacturing of 5G-related equipment, 2019 to 20251

In a second step, we can estimate the impacts of operations, which generally involves looking more precisely at electricity consumption and water consumption related to electricity generation. It is then a question of projecting the evolution of uses, in what order of magnitude the traffic will increase, what part of the population will make the transition to 5G and at what rate? Much of the debate on the ecological impact of 5G has gone in circles by focusing on the power consumption of antennas: yes, a 5G antenna consumes 4 to 10 times less electricity for the same amount of data than a 4G antenna. It remains to be seen how much the traffic will increase and if this increase will cancel out the efficiency gains.

Estimating the environmental impact of 5G is therefore like making an inventory of the additional equipment manufactured and an estimate of the present and future uses of this new equipment. In front of this inventory of material and uses, it is necessary to align environmental data on these manufacturing and use phases. This is the biggest problem of the environmental estimation of 5G, the data is almost unavailable. There are no public lifecycle assessments on new 5G antennas, new 5G smartphones, etc. These data remain with the equipment manufacturers and are largely inaccessible to public research. Therefore, we rely on estimates linked to older but public data. If we cannot rely on 5G smartphone LCAs, we use 4G smartphone data, and so on.

This estimate needs to be reintegrated into a more global analysis framework: are the estimated environmental impacts compatible with an emission reduction trajectory of 5-7% per year, in line with the Paris agreements. Moreover, are the present and future uses of this new technology layer also compatible with this trajectory? Each country is likely to have a different answer depending on the particularities of its telecom network, its energy system, its uses and its transition objectives. In France, the High Council on Climate has issued a public opinion on this issue. It estimated the carbon impact of 5G deployment in 2030 to be between 2.7 MtCO2e and 6.7 MtCO2e (compared to the carbon footprint of the digital sector in France of 15 MtCO2e in 2020). The French High Council on Climate Change has thus judged that the current massive deployment is not compatible with the French emissions reduction strategy and has called for a much more targeted deployment. In Switzerland, at the request of Swisscom, researchers from the University of Zurich have published a technical report on the carbon impact of 5G in Switzerland. They estimate the annual impact of 5G at 0.018 MtCO2e per year. They also argue that the new network could reduce emissions from other sectors through the development of flexible working, smart grids, automated driving and precision agriculture. They estimate these potential avoided emissions to be between 0.1 MtCO2e per year (pessimistic scenario) and 2.1 MtCO2e per year (optimistic scenario). In conclusion, the researchers call for stabilizing the weight of telecoms and reducing regulatory frameworks to unlock the emissions reduction potential of digital technology.

Why do the French and Swiss cases present such different figures: 2.7 to 6.7 MtCO2e / year estimated in France, to 0.018 MtCO2e / year estimated in Switzerland. Not surprisingly for this type of exercise, the difference can be explained by the different scope, reference data and scenarios studied. The French study is based on a mixed top-down/bottom-up approach to provide an order of magnitude on a single factor (carbon from primary energy) by including in its scope telecommunication networks, terminals and part of the data centers (edge computing). The Swiss study proposes a lifecycle analysis of the transfer of 1 GB of mobile data on the Swiss network, its scope includes only network equipment and excludes data centers and terminals. The French report makes the methodological choice not to study the positive impacts due to the lack of available data. However, the Swiss report is unique in that it includes potential positive impacts in the form of avoided emissions. The calculation of avoided emissions is a method that consists of taking a scenario partially enabled by digitization (e.g. teleworking), assigning an avoidance factor (derived from industry case studies) weighted by a theoretical adoption rate (derived from a theoretical matrix from the consulting firm Gartner). This calculation method is, as its methodology suggests, highly speculative and hardly compatible with the rigor of scientific publication.

Conflicting models¶

These two reports highlight a very real tension: if understanding the rebound effects of a technological system like 5G is difficult, estimating the positive impacts is a very perilous methodological exercise. The reports then show two canons of innovation. On the one hand, highlighting the rebound effects would imply re-evaluating and therefore slowing down, or even closing a technological deployment, and therefore thinking about innovation through regulation. On the other hand, highlighting the positive impacts would imply not questioning the current deployment and making it acceptable, thus thinking of a laissez-faire innovation. These two arguments are not new and have been precisely described by historians of technology such as Jean-Baptiste Fressoz and Christophe Bonneuil. However, the current framework invites us to be cautious and not to consider these two paths as equivalent: if we overestimate the positive impacts, then we will continue a process that can be deleterious for the climate, biodiversity, resources, etc.; and if we overestimate the rebound effects, then we will participate in a greater reduction in order to maintain a habitable world. In conclusion, it is the way we define innovation and the economic models that underpin it that creates the virtual lack of technological and social alternatives. The lack of alternatives in public discourse reduces our ability to collectively debate the digital development model in relation to the Paris agreements.

Bibliography¶

Reports¶

-

Gauthier Roussilhe. La controverse de la 5G [online]. July 2020. Available at site [14/04/2021]

-

Haut Conseil sur le Climat. Maitriser l'impact carbone de la 5G [online]. December 2020. Available at site hautconseilclimat.fr [14/04/2021]

-

Jan Bieser, Beatrice Salieri, Roland Hischier, Lorenz M. Hilty. Next generation mobile networks: Problem or opportunity for climate protection? [online]. October 2020. Available at site [14/04/2021]

Books¶

- Jean-Baptiste Fressoz, Christophe Bonneuil. L'apocalypse joyeuse - Une histoire du risque technologique. Seuil, 2012.